|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

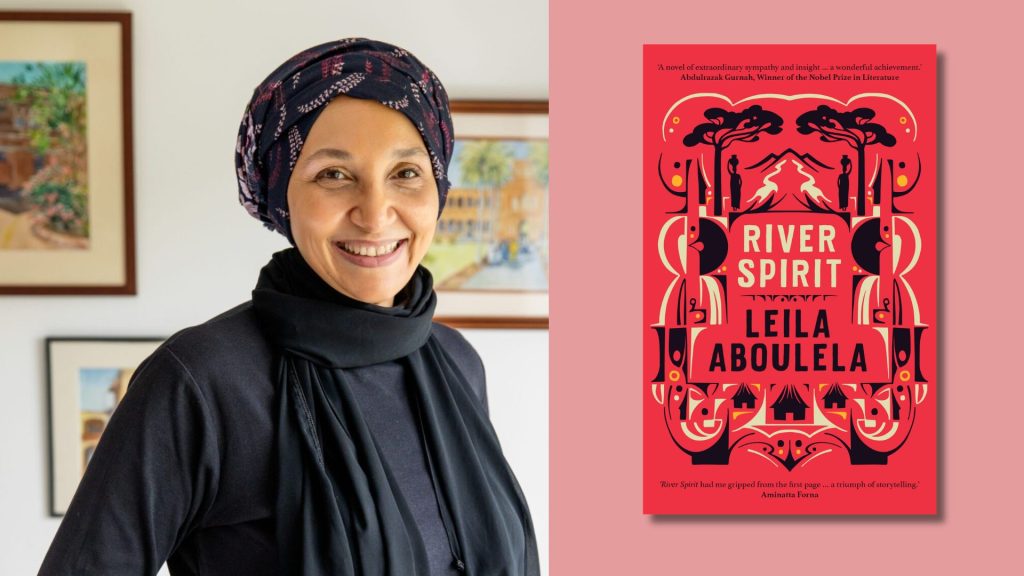

It is our inclination to need, want, desire deeply, desperately for something, someone to believe- in truth or bearing a similarity to truth, whatever truth might be. Leila Aboulela’s River Spirit (2023) transports us to a pivotal period in Sudanese history, 1881-1898, the turbulent years of the Mahdist Revolution, where truth was a fiercely contested battleground. It begins with Rabiha, and her stance, cum ultimately death, for a truth she believes in, the Mahdi. Breathless, after running the whole night, she makes her way through to see the Mahdi but is denied audience solely because she is a woman. The resultant tale is one of defiance, of a woman refusing to be silenced. She catches fire.

“Rage flares through her. She hits out against this wall of belittlement and disregard. Because she’s a woman. Is that why she is doubted? No, she will not be silenced; she will not be brushed aside, not after what she has gone through…”

Although Rabiha’s story is only eleven pages, she defies the narrative against women and goes on to become a ‘rebel,’ and the “woman from Kinana who changed the course of a revolution.” Just like Rabiha, Aboulela sheds the spotlight on numerous women whose stories may or may not have been told through the pages of history. The ones who exist only in the footnotes.

The novel is set in 1800 Sudan when it is sandwiched between the declining Ottoman rule, British-Egyptian influence, and the rise of a self-proclaimed Mahdi. The self-proclaimed Mahdi, Muhammad Ahmed, gains popularity and followers as he publicly objects to many ideas and actions. One of such objections occurred at his teacher, Sheikh Nur al-Daim, son’s wedding celebration where he objected to the music, “brought the party to a halt and offended his teacher’s guests,” and on other occasions, he stood against excessive taxation.

Amidst the chaos, Aboulela introduces us to distinct characters who tell their stories and whose stories are told. There is Yaseen, the son of a merchant who learns the trade but gives up the trade to study in Egypt. During one of his visits from Khartoum to buy gum, the village is raided and he loses everything save for a donkey. He rescues the children of his supplier- Akuany and Bol- with whom he has built a bond. In River Spirit, only perspective matters in war, and Yaseen’s choice is weighed in two lights-

“An adult rescuing two orphans? Or human flesh as compensation for his material loss?”

Throughout the novel, Yaseen’s motives remain ambiguous. While he is perceived to be “the merchant, now Al-Azhar graduate, coming to take back the orphan girl,” he also presents himself as a master, one who pays to purchase a slave in two separate events- the first when Akuany escapes and he asks, “But now that you’ve escaped, why tie yourself to me? Why go from one master to another?” The second is when she refuses to go with him after he’s paid for her release and he addresses her with the tone and diction of a slave master-

“I decide what suits me. You have no choice in this matter, girl. I paid for you.”

River Spirit unflinchingly confronts the horrors of the slave trade. The novel doesn’t attempt to make readers fully comprehend this atrocity, for true understanding can only come from those who directly experienced its cruelty. However, the stories within lend a voice to the ones who were victims, who lived through and died in these times, providing a glimpse of what they endured “homes burnt to ashes, beddings and utensils smashed…the elderly roamed like ghosts…all the vitality gone or going…in the epicenter of the devastation was her father, splayed flat in front of their hut, spared to death.”

She implores a unique writing technique where she switches from 3rd person narrative to a first-person POV, giving the characters room to tell their stories and express thoughts, realities, and actions that would have perhaps been too heavy for anyone to tell, and limited for a third person narrator. Yaseen, Fatimah, his mother, and Musa are handed down the pen to voice their stories and they do it with such grace, inviting readers into their thoughts, feelings, and choices. However, it’s striking to read the main character’s story being voiced from a 3rd person POV and it prompts the question- why can’t Akuany tell her story? Like Yaseen. Fatimah, Musa?

Perhaps it is simply the author’s choice to combine both narrative techniques, then again, the intentionality in her choice communicates a much deeper reason- the distasteful truth that some stories cannot be told by themselves but need to be helped, hence the third person narrative POV. Perhaps it suggests that Akuany’s story is so deeply intertwined with the trauma she has endured. This narrative technique is also used for Robert, a Scottish engineer chasing his dream of becoming a celebrated orientalist painter. Both Akuany and Robert share the burden of devastating loss – Akuany, her father; Robert, his wife. They cling to their passions – Akuany to Yaseen, Robert to his art – maybe as a way to repress the pain of the past. Then again, I perceive Aboulela’s choice of narrative for the main character as a connection with the title of the book. For Akuany, “the river was her language…for her it was …the spirit of who she was.” This alone backs Aboulela’s narrative choice.

The woman, a friend of Yaseen, who housed them for the night during their journey to Khartoum describes Yaseen to eleven-year-old Akuany as her (Akuany’s) “master” and her “virginity” as a precious flower that she “must save” for him. This hardly sounds like an ideal subject for an eleven-year-old or a proper presentation of the relationship that can exist between a woman and a man. This jarring interaction not only highlights the disturbing reality of child marriage that existed in pre-colonial Sudan but also foreshadows its continued prevalence in the post-colonial era.

According to a UNICEF article, in Sudan “most recent figures indicate that 52% of girls are married before they turn 18, with some girls being married off as young as 12 years old,” (UNICEF, 2023). Within Akuany’s thoughts, we see the impact of this cultural practice intertwined with a sense of devotion that blurs the lines of true love. Akauny believes that “she belonged to him” while she also believes that “he was for her and she was for him.” Aboulela portrays the thin line between cultural influence and true love/devotion.

Aboulela’s fantastic depiction of the Mahdist revolt uses history as the foundation of her story and she fills the void with the stories of Fatimah- a widow and businesswoman who shares in the stories of many Sudanese women; Yaseen, son of Fatimah, the merchant who abandons the trade for education in Egypt; Musa, a faithful soldier of the Mahdi who nurses rejection like a sore and from his eyes, we experience the Mahdi. There is Salha, the educated and outspoken woman who refuses to be caged in the way that tradition cages a woman.

Salha, perhaps the most captivating character, embodies resilience. After a difficult divorce from Yaseen, she dedicates herself to empowering other women by educating them about their rights, including the right to pray alongside men. She highlights her father as the silent hero whose decision to send her to the kuttab (maktab) alongside her brothers empowered her. Her journey stands in stark contrast to Akuany’s. Despite their shared affection for Yaseen, Salha demonstrates the ability to redirect her emotions and forge a new path. While Akuany remains the titular character, Salha leaves a more profound impression.

The novel concludes on a bittersweet note. Salha’s letter to Akuany recounts the events of 1898, including the victory of the British & Egyptian armies in Khartoum. She expresses her sincere condolences for the death of Ishaq/Bol (Akuany’s brother). However, Salha doesn’t dwell on the sadness. Instead, she chooses to remember Ishaq with a vivid image: “the grand bridegroom—stamping in the circle of dancers, with the kohl rimming his eyes and fresh henna on his feet, raising his sword in the air, and jumping.” This final memory encapsulates Ishaq’s vibrancy and spirit, offering a sense of solace amidst the loss.

If you’re looking to delve into Sudanese post-colonial history through the lens of its people, River Spirit offers a captivating and multifaceted exploration. I highly recommend it.

Glossary

Kuttab/Maktab: A kuttab (Arabic: كُتَّاب kuttāb, plural: kataatiib, كَتاتِيبُ) or maktab (Arabic: مَكْتَب) is a type of elementary school in the Muslim world. The kuttāb represents an old-fashioned method of education in Muslim-majority countries, in which a sheikh teaches a group of students who sit in front of him on the ground

Mahdi: The Mahdi (Arabic: ٱلْمَهْدِيّ, romanized: al-Mahdī, lit. ‘the Guided’) is a prominent figure in Islamic eschatology who is believed to appear at the End of Time to rid the world of evil and injustice

References

“Kuttab.” Dbpedia. Retrieved April 18, 2024, https://dbpedia.org/page/Kuttab

“Mahdi.” Wikipedia. April 2, 2024, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mahdi

“Ending Child Marriage Should Not be a Choice but a Necessity.” United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF), 8 December 2023, https://www.unicef.org/southsudan/stories/ending-child-marriage-should-not-be-choice-necessity

Photo if Leila Aboulela by Judy Laing