|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

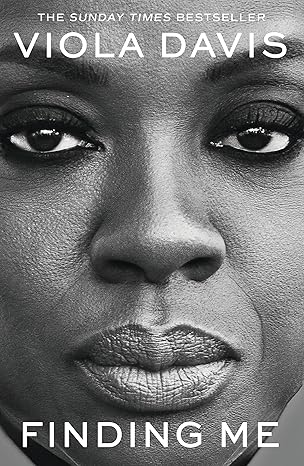

I have always believed that actors have more to tell about themselves than the characters they portray. They often project pieces of themselves into each role, allowing them to express emotions with remarkable authenticity. While my opinion is not grounded in research, I have seen it unfold countless times. The same can be said for authors—Chimamanda Adichie in Americanah comes to mind, where her fictional characters feel rooted in experiences far deeper than mere imagination. Viola Davis’s memoir Finding Me affirms this belief, showing how identity, trauma, and resilience shape not only the performer but also the person beneath the roles.

The opening chapter, Running, captures the image of a little girl sprinting home from school—not in joy, but in fear. Boys chased her, hurling hatred because of her Blackness. Yet she is not the only one running. The Portuguese boy who chases her is also running—from a racial identity he neither understands nor accepts. This complicates the often-repeated claim that “Black people cannot be racist.” As the Jim Crow Museum explains, whether that statement is true depends on how racism is defined. If it is prejudice and discrimination rooted in race-based loathing, then yes, anyone can be racist. But if it is understood as a system of privilege maintained by those with disproportionate societal power, the definition changes. Viola’s recollection, and the world her mother Mae Alice inhabits, reveals how racial constructs can shape lives across generations—the kind that make school unbearable and force little Black girls to run home.

Running, however, does not always solve the problem. Sometimes we must face the elephant in the room, even while masking fear with anger and exhaustion. Mae Alice’s life also draws attention to another pressing social reality: the high rate of teenage pregnancies among Black girls and the way they can alter futures. She had three children between the ages of fifteen and nineteen—years that might otherwise have been her own time to grow and dream. This is not to diminish her resilience or the eventual beauty of her life, but to acknowledge that some struggles and traumas could have been avoided. The statistics are sobering; CDC data shows that teenage pregnancy and childbirth rates have historically been highest among Black, Latino, and Native American youth. Against this backdrop, Mae Alice’s story becomes more than personal—it becomes emblematic of broader systemic patterns.

What makes Finding Me so immersive is Viola’s deliberate, unflinching style. She appeals to the senses, creating vivid scenes that draw readers directly into her world. She describes her childhood living conditions with raw precision: “The plumbing was shoddy, so the toilets never flushed… I became very skilled at filling up a bucket and pouring it into the toilet… We were often without towels, soap, shampoo…” Her use of African American Vernacular English—words like “yo,” “gotta,” and “ya”—adds cultural texture and authenticity, making the memoir not just a recollection but an initiation into the lived realities of many Black women.

One of the most transformative points in Davis’s life came through Juilliard, where she says she was forced to understand “the power of my Blackness,” even as she endured trauma and insecurity. Her healing deepened during a trip to Gambia, which she describes as “transformational.” The sense of community and belonging she experienced there restored the creative potency she had lost within the Eurocentric standards of her training. In that space, she embraced a truth that would define her artistry: “There is no creating without using you.”

Davis does not shy away from exposing Hollywood’s inequities. Even after two Oscar nominations, she found herself excluded from the kinds of roles routinely offered to her white—and even some Black—counterparts. The bias was not subtle; her skin color was as much a barrier on screen as it had been in childhood. The role of Annalise Keating in How to Get Away with Murder was a breakthrough, but not without resistance. Industry voices questioned her suitability for a leading lady on network television, revealing the quiet but persistent standard that one must either be a Black female version of a white ideal or be white altogether.

For viewers who have been enthralled by Annalise Keating, it is important to understand that the power of the character lies not only in Peter Norwalk’s sharp writing or Shonda Rhimes’s production brilliance. Viola Davis breathed life into Annalise, shaping her into a woman who could reconcile with her eight-year-old self and embark on the journey that gives the memoir its title: Finding Me.

In the end, Davis’s memoir is more than a personal account—it is an unflinching examination of race, womanhood, and the courage to claim one’s identity in a world that constantly tries to rewrite it. She shows that the roles we play, whether on stage, on screen, or in life, have the most power when they are rooted in who we truly are.

Resources

Ferris State University. Can Black People Be Racist? Jim Crow Museum of Racist Memorabilia, Mar. 2009, jimcrowmuseum.ferris.edu/question/2009/march.htm.

“Teenage Pregnancy in the United States.” Wikipedia, Wikimedia Foundation, en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Teenage_pregnancy_in_the_United_States.