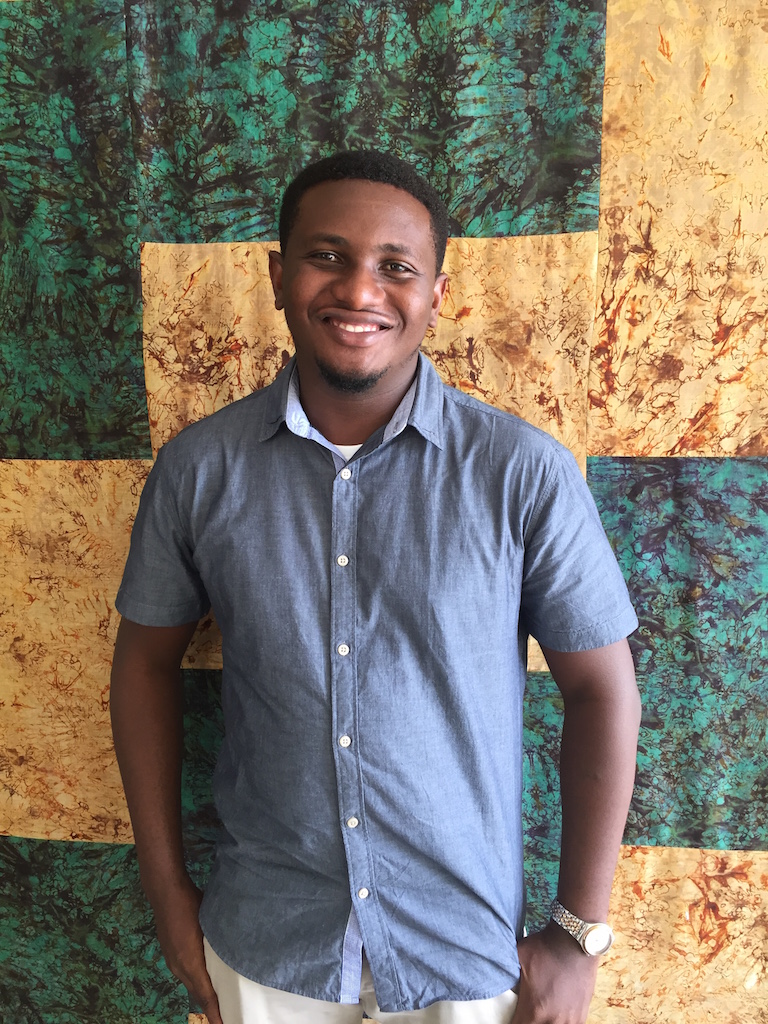

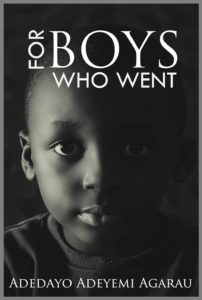

Adedayo Agarau is a student and poet hoping to make the world a little better with his words and photography. He has works up at Barren Magazine, Geometry, Glass poetry, 8poems and elsewhere. He is the author of For Boys Who Went. Our Editorial Intern, Oluwapelumi Sàlàkó had a chat with Adedayo Agarau.

Salako: Good day, Adedayo. A little background prodding: Why do you write, how did you discovered writing and does it come easily to you?

Agarau: Without having to sound woke, writing and friends are the reasons why I am not dead. It was first a getaway, a hobby that keeps me more to myself than dangling away in the winds. But it soon catapulted into a form of existence. Or rather, the medium through which I live, express and leave. When I found Rasaq’s Poetry in 2012, I knew I wanted to tell my stories too. I wanted to talk about the girl whom I desperately loved by wouldn’t love me back. So, I wrote my first poem. But I guess I grew to be more selfish about my writing. Found writing as the sunflower, mild, vulnerable, yet beautiful. Writing is one of the reasons why I am never alone; it is my companion.

And does writing come easy? With a bulk of bad experiences that keep pushing me back to my childhood, with depression and the big work of survival? No! Writing does not come easy. Just few days ago, a friend and artist, Mahmood, told me he learnt to check up on writers since he realised they sprinkle ounces of their details around their works. Truth is a hard pill or a virtue too hard to give away. But I give it anyway.

Salako: Why do you write about the sort of things you write? I asked because your poems are multifaceted, and your writing tailored towards a certain perspective. Is that a deliberate or subconscious part of your craft?

Agarau: How I drifted from being the love poet to someone who is always looking back through the window of childhood is what I don’t know. But I am here. Reality check: I am grateful for everything that happened to me. Writing about them now, I figured how beautiful, bold, strong and courageous a cub is. Little does not mean weak or dead. Other times, I intentionally drift towards capturing hearts and bringing them into a state with me. Art is art anyway, so we are allowed to create a world for our readers; the world where we evolve and are allowed to dream. I once wrote a poem about a girl that was married off at a tender age and the next day, an old man in Northern Nigeria married a young 11 year old. I cried and carried the guilt for days and more. We have been ordained as the angels of the earth, poets, we have been given the vision so we run with it. Writing is a conscious effort, and the deliberate act grants you the liberty to trap deep into the countries lying beneath the skin.

Salako: Your writings feed on imagination, memory and experience and you write mostly in the first-person narrative. I believe that poetry is an art of storytelling. Who are the owners of the stories you tell? Who is the speaker in your poems?

Agarau: When Walter Raleigh wrote Go Soul, he wrote using the persona of a dying man’s soul. Poetry as an art is a beauty. It allows you, in whatever narrative you write, to stand away from the poem and let the persona act the drama, say the words, coin the imagery. At some point in my life, I made peace with letting myself grow out of the storm because it is from there strength rises. The speaker in most of my poems is an emotionally fucked-up boy learning to love himself, learning to stiffen up, taking rejection as a form of solitude. This boy, in recent days, is growing stronger, less depressed, looking out for depressed friends, writing for friends who are popping pills but yet, surviving. It is a hard trade! Writing is like taking one’s self to the gallows to hang for Christ’s sake. Then rising with a done poem, like a saviour, like the one destined to save the earth. But the process is not friendly.

Salako: I read your poem about an abused child when it was first published on Brittle Paper. The language diffused in that poem is highly evocative and while reading, it felt personal and has stayed with me. Somehow, I have a reason to believe that you have experienced that event first-hand. In writing out your reality, does it heal or open up the scars?

Agarau: Opened scars heal faster. Since the poem was written, I have cherished my brave self. I never underestimate myself anymore. Open scars heal faster. But the poem redefined how people saw me, my experience, not as weak, but as a poet who is strong enough to recount a shattering experience. The poem is still with me. And not just the poem, my experience is still with me. The concept of healing is not cover your pain and excel.

Writing about these mean to me that I share my hurt with the world. A world ready to suck it in and make it theirs. It’s a lovely world we are in.

Salako: Who are the most important writers of your life and what sort of writing fascinates you?

Agarau: Savannah Slone, Elisabeth Horan, Abdulraquib, Safia Elhillo, DM Aderibigbe, Logan February, Saddiq, Salawu Jide, Hauwa Shaffi. The list is quite endless. However, I have an inner circus of writer friends who stand by my writing. Kanyinsola Olorunnisola, Nome Paht, Michael Akuchie, Taiye Oguns, Mesioye Johnson and Wale Ayinla. Their works are tender but very evocative, just the way I love it.

Salako: In reading these writers, what do you look out for and what is a good poem to you?

Agarau: Truth.

Good poetry is subjective. Is there a bad poem? No! But some works are badly written. Good poems for me are works that wash me ashore, yet drown me at the same time. I was reading to myself sometime and my neighbour came to knock to say I was actually screaming the lines. I remembered I was reading Nome’s work at that time. Good poetry spreads its fingers across the body and pinches you in places where it hurts, where it soothes. Good poetry is just good poetry, nothing else.

Salako: You as a photographer. What moved you to documenting Ibadan? Can you discuss the relevance of your photography to your poetry, how does the two art forms complement and did you first become a photographer before a poet?

Agarau: I like to agree that I am from a lineage of creatives. My grandfather, who died in 1995, was a photographer and a songwriter. I am constantly on the hunt for stories. When I started the Walls of Ibadan Project, it was away from just taking photos, I wanted to gift Ibadan stories to the media. The narrative about the city is stale and dead so I started the project to retell the city itself and the people therein. Photography and Poetry are nose and air, they save the day.

Salako: In this period of popular depression and harsh realities, how do you navigate the storm? Have you experienced depression? What do you do with it?

Agarau: Depression! I write with my depression, give myself grace when I can’t. It requires artistry. I am learning to grab hold of self and never let go but while we are at that, I am still here writing and taking photos.

Salako: Thank you very much for your time. Awards should not validate our proficiency as writers but the fortunes that accompany them are very important and they most times serve as yardsticks in measuring our career. However, I will like to know your personal sentiment on this subject.

Agarau: Awards do not and will never validate your ability to write. Competitions are judged based on the judge’s preference. There are good poems that will win a thousand times. Award is great! I have won a few. But what works come after.

Agarau’s manuscript “Asylum Chapel,” is coming to light for publication and looking for a good home. Please connect with him on twitter @adedayo_agarau and on Instagram @wallsofibadan, where he documents the beauty and pain of his Nigerian city home.

Olúwapèlúmi Francis Sàlàkó writes from North Central, Nigeria. His writings aim to interrogate the place of memory, loss & love, stereotype, culture and history. He has works up or forthcoming at Ngiga review, Prachya review, Dwarts, the rising phoenix review, elsewhere. He is a 2017 recipient of the Green author prize.