|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

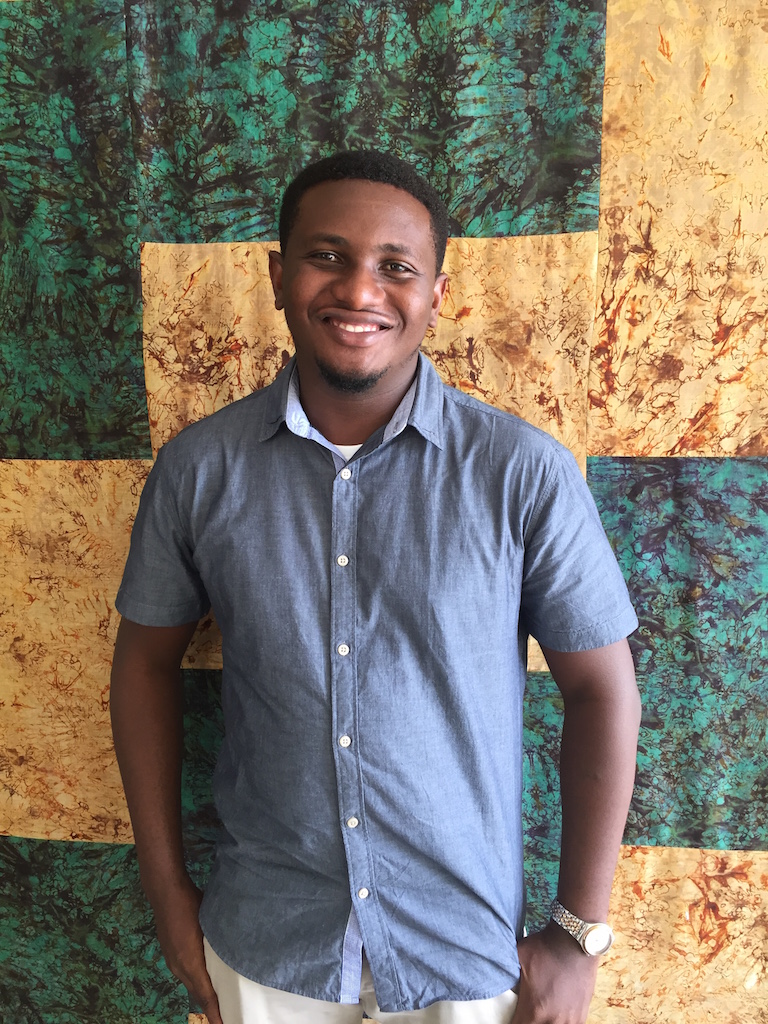

There’s something profound about Tares Oburumu the moment you ask him a question and he begins to respond. Maybe it’s in his eyes. Maybe it’s in the way he hangs his head, but you’d just feel that there’s something, even if you can’t quite place it. As the conversation threads along, you will then come to realize that he’s a deep thinker. I may explain that as foundational to his roots in Philosophy, but I’m not sure who found who, if he found philosophy or it found him.

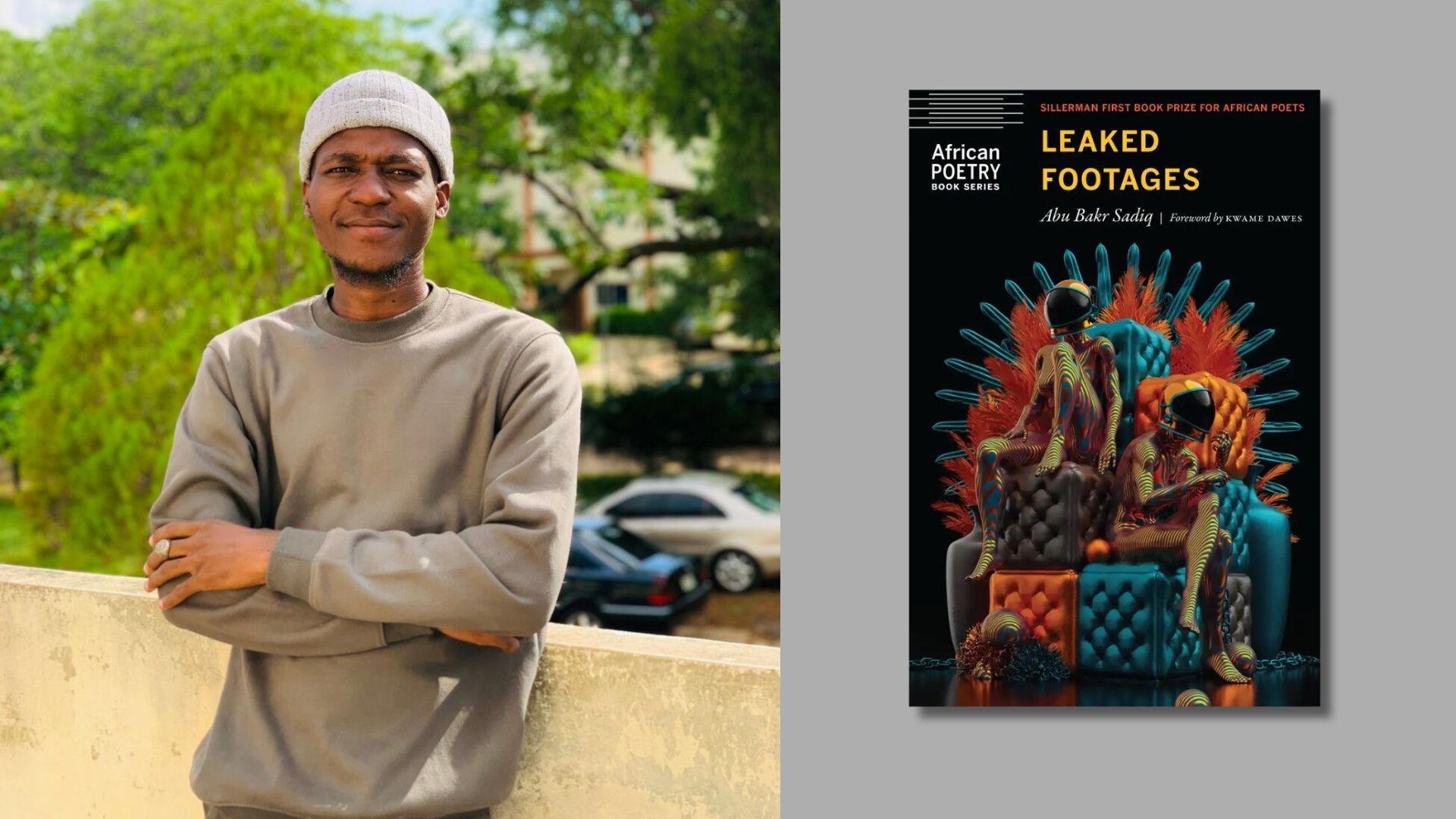

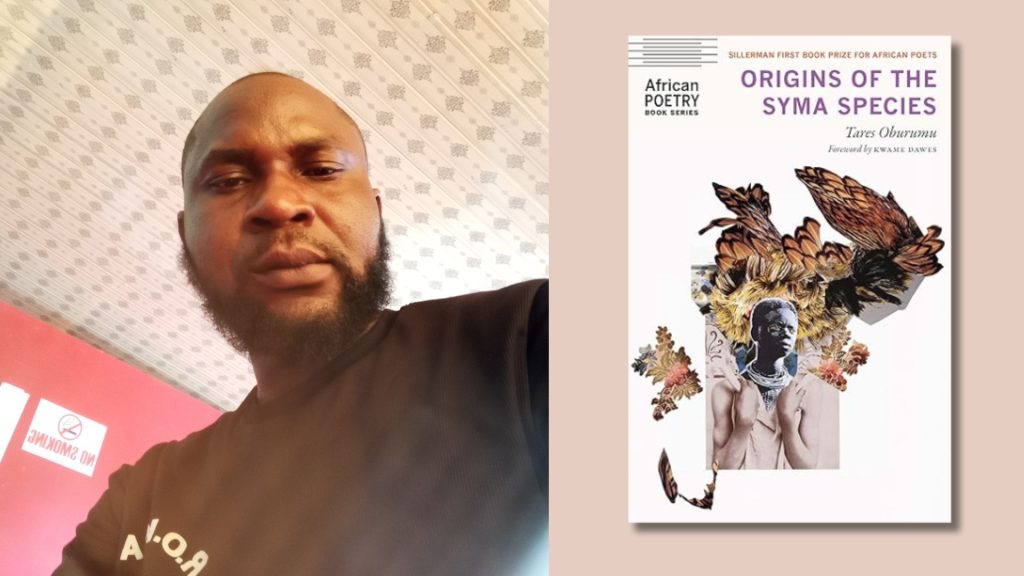

In 2022, Oburumu won the Sillerman First Book Prize for his manuscript, Origins of Syma Species. The book wasn’t his first manuscript but it would be the one that ushers him into the poetry landscape. I first met Oburumu at the 2023 Lagos International Poetry Festival where he was a guest on a panel with Abu Bakr Sadiq. Both were on a panel discussing contemporary African poets and the mechanics or writing to a modern audience and winning poetry prizes.

I began this interview by asking Oburumu to tell me about himself, it’s the logical place to start. A name. A place. A face. An identity. And you could tell from his response that that is not a question to respond to in a rush. Oburumu begins by saying, “I have been asking myself that question too…” It’s “… just as complicated as the answer.”

It’s nothing to fret about though. He answers the question “in the light of identity.” He’s a Nigerian “of the Ijaw extraction. Born and bred in Delta; a little of Urhobo” and then goes cloaks and daggers, “a little of one other I can’t mention.”

Tares, his name, is a derivative of Tare. He tells me that while in school there were many people bearing Tare. And out of the need to be different, he added an “s” to his Tare, becoming a plurality, “an umbrella under which all love, or Tare [Tare means love] existed.” Oburumu feels that a name goes beyond individualizing us. It is spiritual. Of course the social elements too cannot be discountenanced. For a moment though we let the talk about names simmer, while I ask him to share the moment he got the call or email informing him he had won the 2022 Sillerman Book Prize.

The Sillerman First Book Prize, run by the African Poetry Book Fund, is awarded annually, since 2013, to emerging African poets from across the continent and the diaspora, in partnership with the University of Nebraska Press. Oburumu is the tenth poet to have been awarded the prize (the 11th would be Abu Bakr Sadiq, who won the 2023 prize).

So he says the notification arrived in his inbox. “On that night, I was reading through some of my poems published in a few journals….” Why at night? Tares is not one to hold back from telling you how it is. He shares that it’s because that’s when he has access to a phone. “I was lifted high by the arms of the small world I had known into the Homeric.” If you think he’s a hard man, hold that thought! “A scream escaped” my lungs, “and woke up my fiancée. We both embraced in a moment that was awkward between us; we just had a bad fight a few days ago.” I guess you know now that winning prizes break walls. And then he concludes by saying the “feeling still dumbfounds him till date.” Yes, Oburumu, you have actual copies out there! I’m probably more excited than he is!

Let me put this simply, the question I asked him next: in that space (the moment you got the email) if there was one thing you’d have reached for, what would that be? I asked this question because moments like that bring their weights and nostalgia. Like that “Acknowledgment” page on your thesis!

Here’s Oburumu’s response: “my mother…” She’d have been the one thing he reaches for. “…she’s my poetry…so close yet so far at that moment.” You are probably thinking like me if there’s a poem or two in his book dedicated to her. Tares did mention that the day his personal copies arrived, he called his mother up to inform her. And, copies of Oburumu’s book, Origins of the Syma Species are out this month and you can grab them here.

One of the uniqueness of Nantygreens as a literary blog is the opportunity we accord poets at different stages of their craft. Many of the poems you read here are not burnished from the get go. They had to be edited, sometimes requiring a back and forth correspondence before the final digestible piece is published. So I asked Tares—because we really need to know what the journey’s been like for him—to tell us how long it’s taken him to arrive here, the winner of a prestigious poetry book prize.

“Years,” he says. He elaborates further. “Ten grueling years of experience, …consistency, solitude, suicidal thoughts, depression, frustration, begging for money among other things, childbirth in between.” That’s a lot, man! And therein lies the triumph: even if each poet’s path or journey is different. This might not just be a book then. It might just be a birthing. So I asked him if he ever thought to give up or stopped to think that he could ever publish a poetry book. And then he waxes plainly, almost epochal, “I wasn’t built to break.” He did try to give up he admits, but then he says, “I don’t know any other way to drain the blood that flows in me.” In between these thoughts he quipped that he sometimes thinks of himself “… as a baby” and was awestruck by his winning the prize.

The judges praised and name as finalists manuscripts from Chisom Okafor (Nigeria) Winged Witnesses, and My First Country Was My Mother, Afaq (Sudan). These are notable emerging poets too, and especially am I familiar with Okafor’s work. Well, you also can’t miss him, he’s a regular face at poetry workshops at literary festivals.

I wanted to hear from Oburumu if he’s familiar with them too and if they’d inspired him as well. With much assuredness he opines that “if there’s a poet writing in Africa that he doesn’t know, it’s because they haven’t given a song to their voices. And admits that he “couldn’t have become who he was, who he is, and who he will become, without reading these poets.

Like Oburumu, our expectations for Syma are high. And he concludes the thought by saying that “when you are recognized by reputable people, you don’t have to worry about anything.” His new book is fine wine.

I will allow his voice to carry on further.

“I have always believed in the personal; pouring myself, my blood into whatever I do. I have to tell my story because no one else can tell it better than I do. I write about myself, which resonates with a million people and things. Much of what I write are personal experiences. During the formative years, someone sent me a message from Susan, a Sudanese, how a poem of mine saved him. Shared stories, shared experiences give ample balance in subtle and most tremendous ways. If there’s anything I have learnt in my years of writing poetry, it’s the self having other selves in people and things. When you think you are telling a story or your own story, you are telling a thousand stories for the thousands who cannot tell it by themselves. If there was a better way other than mine to tell my story, I wouldn’t have been doing poetry.”

My final questions were a dive into possible work on the horizon and if there’s any poem in Syma that keeps him on the edge. He says, “Let There Be Lamplight” would be the poem that keeps him on the edge but doesn’t say why. And concludes by saying he has “Not one” but many works forthcoming, even before Origins of the Syma Species. There’s more to look out for from Tares Oburumu.

Origins of the Syma Species is out and can be ordered here.