ELEGY #1

All beginnings have a whiff of an ending, a sign of an impending halt. It lends a temporal feeling to all things that are. It illuminates the absurdity of existence, for all things that are will one day no longer be.

But perhaps death is not an ending but a new beginning.

What new beginning could my sister be experiencing now that she’s dead? And what does that beginning look like? Is it made of roses, of a foggy atmosphere, or of a crimson color reminiscent of blood?

ELEGY #2

Every grieving eventually wears itself out. Prolonged bereavement is unseemly. There’s an ending to the mourning of an ending. Roland Barthes once wrote about the measurement of mourning, alluding to the idea that there’s a time limit to mourning.

ELEGY #3

How do we process death? How do we make sense of it? Is it through writing? Is it through meditating? Is it through reading? These are the questions I asked myself shortly after she died. These are the questions I still ask myself.

ELEGY #4

The death of a loved one leaves something irrevocably broken in us. It lacerates our being. And our lives become nothing more than an aggregate of all that has been broken, all that has been lacerated.

ELEGY #5

It is easier to speak about death in elliptical terms, to speak without really saying anything.

ELEGY #6

She’s dead. She died. The finality of these words, succinctly describing the irremediable. Writing about the death of his father, Carl Jung describes the feeling we get after losing a loved one as an ‘icy feeling’. I could relate to that. Following the death of my sister, I felt like I had been out in the cold for too long. I felt like I was freezing with grief.

ELEGY #7

Why do we reminisce so much about the last thing we said to someone before they died? Why do we torture ourselves over this?

The last conversation we had was about the danger of walking the streets in the dark. We had only just arrived at our new house a few hours prior. We were standing on the balcony and she told me that something about the new neighborhood made her uncomfortable. She said that for no reason would she walk the streets in the dark. She was worried that she would be mugged or murdered.

ELEGY #8

The death of a loved one leaves us with a feeling of impending doom. We begin to imagine that more people are going to die, as though one death begets another. For a while after she died, I had this terrifying feeling that someone else was going to die.

ELEGY #9

All deaths are difficult to deal with. But sudden death? Seemingly out of nowhere? It’s devastating.

ELEGY #10

‘Was there blood?’ a psychiatrist asked me after I had just finished talking about the death of my sister. ‘No.’ I responded.’ No. There was no blood.’

Years later, I would ask myself what the significance of the psychiatrist’s question was. Why does it matter if there had been blood? Is a bloodless death less painful than a bloody one?

ELEGY #11

Here’s a memory: she walks into our father’s room to inquire about something. Our father comes out smiling. He tells us that the way she pronounces certain words is funny. We ask her to pronounce the words, and when she does, we all start giggling.

We would joke about this incident for many years to come. But not after her death. All jokes cease after her demise. Even my brother, who was sort of like the family jester then, is now decidedly unfunny. Death lends an air of melancholy to everything and to everyone.

ELEGY #12

There was a framed picture of her on the wall. I used to be envious of the fact that she had a framed image while I didn’t. In the photograph, she is wearing a shirt and a pair of trousers. At first glance, you usually couldn’t tell if the person in the picture is male or female. We used to joke about this too.

I will like to behold this picture once more but I have no idea where it is now. It’s gone. Just like my sister

ELEGY #13

South African comedian Trevor Noah once said that comedy is his way of processing pain. Of course he would know a thing or two about pain, considering the fact that his mother was shot in the head. Miraculously, Trevor’s mother survived, but Trevor would be forever scarred by this incident. Comedy, he reiterates, is how he deals with grief. But does comedy really alleviate pain? Does laughter really ameliorate grief?

Shortly after my sister died, a friend of mine, Solomon, called me and during the course of our conversation he ‘cracked a joke.’ This is a guy who, all things considered, is very funny, a guy whose jokes had made me laugh on several occasions. But I didn’t laugh at his joke then.

In a voice betraying all attempts to feign complacency, I said, ‘ My sister’s dead.’

Death renders comedy mute.

ELEGY #14

How did she die? I had thought it was silly for people to ask this about someone who had died. Family members of the victims of a plane crash, relatives of people who died in combat, they all want to know how their loved one died, as though the manner of dying is more important than death in itself. But after the death of my sister, I came to believe that there’s a certain significance to how a person dies. How did she die? I have had to explain this countless number of times. Sometimes to people who didn’t really ask.

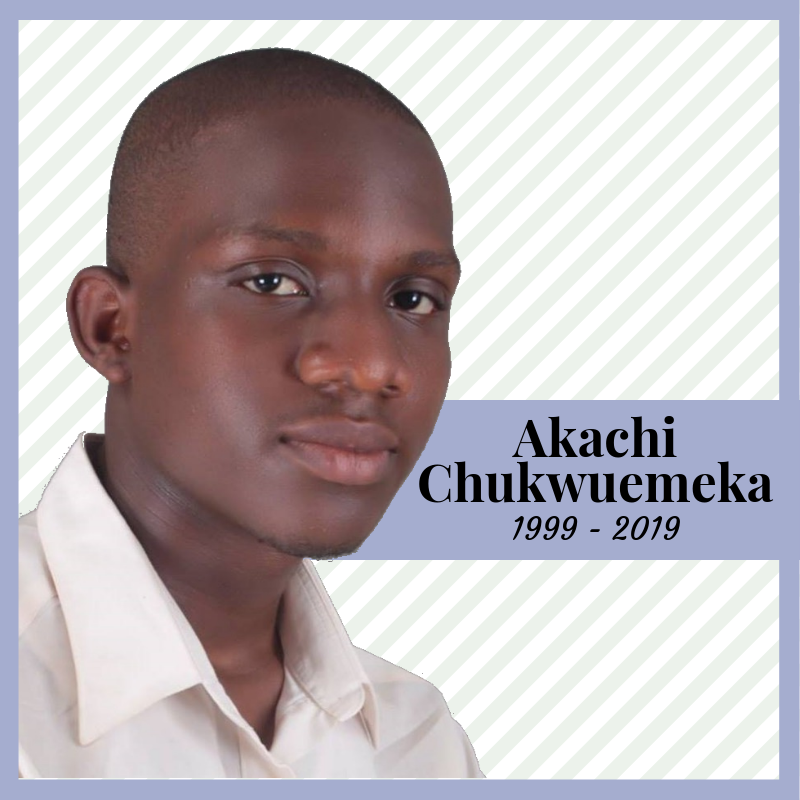

Here’s how she died: she was stricken by a heavy piece of metal from a parked truck. The metal hit her neck, fracturing her hyoid bone , damaging her trachea. Her brain most probably was deprived of oxygen for about an hour before someone finally ‘found’ her body. She probably suffocated to death.

I use the word ‘probably’ because we don’t really know the particular details about how she died. We just found her lying there, with the metal on her neck, her face swollen, her tongue sticking out, a gruesome image to behold. But there was no blood. No, there was no blood. Thank God for small favors.

ELEGY #15

Was her death an accident? Or was it suicide? Did she intentionally dislodge that piece of metal knowing that it would kill her? Had she wanted to die? Nietchze recommends a voluntary death, a death which comes because we wish for it. Had she wished for death?

ELEGY #16

People say that she was depressed a few weeks before she died. They say that she was seen standing on the balcony, looking morose, contemplating her life. Or perhaps she was contemplating her death? I do not know whether she really wanted to die. What I do know is that there are easier ways to kill yourself.

ELEGY #17

In med school, we were taught how to notify family members that their loved one is dead. Find a secluded spot. Make sure they are sitting down. Do not use vague expressions like ‘ passed away’ or ‘ no longer with us’. Be direct. Tell them that their loved one is dead. But as much you are to be direct, you are also to be compassionate.

ELEGY #18

Writing is the only way I know to grieve properly. I cry letters; I weep words. I waddle in this pool of letters, in this ocean of words. And I take whatever comfort they might offer.

ELEGY #19

Death takes something from us, a pound of flesh, a piece of our soul. How do we regain that which has been lost? This is the heart of the matter when it comes to dealing with grief, that we are forever yearning for that which we will never behold. If all grief must come to an end, then what brings about this ending? What engenders it? And how is it sustained even when we are staring far into the horizon to glimpse the one we have lost? Perhaps the only true ending to bereavement is our own ending, for all who grieve for the dead must one day face their own death.

ELEGY #20

My younger brother has let me know that he is no stranger to death, deaths both sudden and slow. He speaks of the boy who went swimming with friends and drowned. He speaks of the man who was cut into half when a truck ran over him. He speaks of the boy who fell from a height, cracking his skull on impact, splashing blood and brain matter on the gravel. He speaks of those who met a violent death, those who were yanked out of this world with a certain forcefulness, a certain brutality. On slow death, he tells me that he has been present during the solemn passing of a distant relative. It is less gory, he tells me, but there’s also something heart-breaking about seeing someone take their final breath.

ELEGY #21

Before the death of a loved one all deaths seem distant to us. I vividly recall, while growing up, memories of distant deaths. When I was about eleven, there was a death which happened just a few blocks away from our house, a young lady who was raped and murdered. Her body was found by the side of the road, stripped of essential clothing. When I was about thirteen, one of our neighbors adopted a child whose biological parents had died. The adoptive parents had been together for many years without a child, perhaps that was why the man had taken up drinking, perhaps that was why the woman grew forlorn. But the coming of the adopted child, a bright little girl they called Kosi, lit up their world. Kosi brought laughter to their lives. However, shortly after Kosi’s arrival, the man’s drinking buddy died, then a short while later, the man died. The woman had not yet even mourned her husband for a year before she too died. I could remember the day they took away the woman’s corpse, the last living adult in the house. I watched this family live and I watched them die. The intrigue of observing distant deaths.

ELEGY #22

Prophet Mohammed referred to the year he lost his wife Khadija, the same year he lost his uncle Abu Talib, as the year of melancholy. We often spread our grief over time. Or perhaps it spreads of its own accord, over months, over years, over decades, scattering pebbles of sorrow over a vast landscape. Grief is not easily curtailed; it is not easily contained.

ELEGY #23

True grief is that which is felt to the bone. But unyielding though our bones might seem, it eventually gives in to the weight of agony, fracturing our metaphysis, damaging our marrow, leading us to even more agony. Perhaps this was why, during the months following my sister’s death, I was rendered immobile, a necessary catatonia. True grief makes brittle bones of us all.

ELEGY 24

The grief-stricken must not not be made to bury their dead. This is the worst of all torments. Shortly after my sister died, I was told to go along with my brothers to the funeral ground to bury her. Perhaps they thought burial was a way of letting go and that the sooner I let go the better. But instead of letting me let go, participating in her burial further scarred me. I will forever bear in my mind, the image of her body enshrouded with a white piece of cloth, her body rolled into the grave. We are all too quick to dispatch the death, with a delusion that we are severing our ties with them, sending them off to another world. A delusion, I say, because the dead have a way of holding on to us as much as we might want to let go. The dead have a way of holding on to us as much as we hold on to them.

ELEGY #25

A grief deferred must eventually be reckoned with. A few days after my sister died, I walked into my father’s room and said,’ I want to travel back to Enugu. I want to go back to school.’ He was taken aback. He had imagined that I would stay for the duration of the mourning, particularly seeing as there was nothing really going in school. So why did I want to leave so soon? I couldn’t explain it. I just had to leave. I just had to get away from all the crying, all the wailing. So I went back to school and I screened all calls coming from home. I wanted to be alone. I wanted to do away with grief, to keep mourning in abeyance.

But not for long. I had just been in school for a few days when, on listening to the Coldplay song Fix You, the memories of my sister’s death were awakened. I broke down and started weeping uncontrollably. This was the first in a series of break-downs to come. Finally, I was forced to reckon with my grief. Even now, whenever I think of her death, whenever I see death being portrayed on TV, I still go into a fit of uncontrollable crying. Once, I was watching a documentary about the Columbine shootings and on hearing one of the survivors speak about the death of his sister, I started weeping uncontrollably. A fit of uncontrollable crying, prompted by portrayals of death, is there a cure for this? Or has the death of my sister left me with an incurable condition?

ELEGY #26

‘She would want you to be happy.’ people said to me months after my sister’s death.’ She would want you to move on.’ Except that my sister doesn’t want anything now. She’s dead and the dead do not want anything. I am now left to navigate this veil of grief, to carve out a path in this looming darkness.

ELEGY #27

The aftermath of a death. Those left to grieve. The wailing. The insurmountable pain.

ELEGY #28

I have often found myself standing at the edge of the precipice, willing to plunge into the abyss. But so far I have managed to restrain myself, to keep myself from diving into death. Deferring death, I chose life. Yes, of course I chose life. With all the pain and sorrow enclosed within.

Nawawi Sani-Deen is a writer from Nigeria. He is an avid reader of contemporary fiction, lyrical memoirs and essay collections. His literary heroes are Kate Zambreno, Mohsin Hamid and Orhan Pamuk. Follow him on Twitter @NawawiDeen.